Reflecting on my failures

I was able to see myself clearly, maybe for the first time, during my sabbatical.

It wasn’t pretty.

—

I think it was all the time and space I had to think.

And the comparative level of maturity that I’d developed over time to be able to hold myself with unconditional self-love and self-respect.

It is only with unconditional self-love and self-respect that one could see oneself clearly enough.

That is the only way you can be safe without the armor of stories and identities one has built around oneself out of defensiveness and fear.

Otherwise the terrain is too fraught, too risky.

One could get eaten by the sharks of shame.

One could get buried under an avalanche of self-loathing.

—

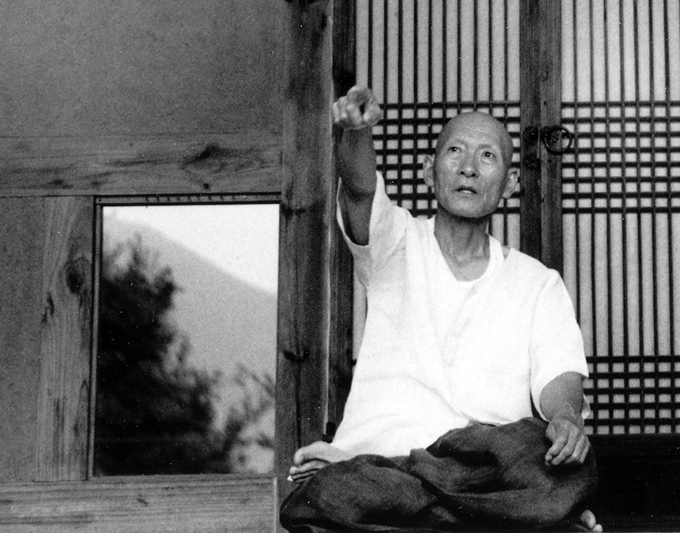

In sabbatical, I spent a lot of time with the teachings of Zen masters.

Ones that had guns pointed at them. That had willingly spent time in prisons. That had taken vows of poverty. That had risked their lives for the oppressed. That had recited the sutras and spent thousands of hours in meditation and then actually flexed the power of their titanium-grade spiritual backbone in real life.

If only people knew what “mindfulness” is really capable of in Mahayana Buddhism.

It was actually breathtaking, thinking about how green and shallow I have been in comparison.

(What’s more breathtaking was how unaware I had been of that fact.)

What an impudent little poseur I had been, thinking that I was some kind of hot shit, doing something profound, changing the world!

I also saw the limitations of my personal character with brutal clarity.

My irascibility. My imperiousness. The sloppy command over the formidable instrument of my own mind that led to so much ‘leak’.

This was all felt, once again, with zero unkindness toward myself.

Rather, I felt like a child who scaled the neighborhood hill, proudly planted the flag I’d painted at home, then looked up to discover Everest.

The ferocity of my feeling was not hatred against the version of myself who climbed the little hill, but a fire that was a love of climbing.

I saw higher.

Infinitely higher.

I was humbled.

It felt terrible.

And deeply, deeply cleansing.

—

I had read the excerpt of Alexei Navalny’s memoir, which sent me down a rabbit hole of reading the epistles of Occupied Korea’s own freedom fighters on death row.

My husband argued with me. “I don’t believe for a second he actually wrote that stuff from prison in the Arctic. How’d he get it out?”

But it actually didn’t matter to me whether he really did write those words in prison.

There were plenty of others before him, and there will be others after him. In Russia. Turkey. Iran. Both Koreas. Palestine.

What mattered to me was the example of fierce moral clarity and courage that slice through the haze of willful oblivion, selfishness and greed that cloud our collective vision. The dry Russian wit — in the midst of it all!! — was just a heartrending cherry on top. (He cracks jokes with his prison guards!)

What a man.

—

Navalny died for a free Russia.

“What are you willing to die for?”

That is a horrible, distasteful, inhumane question.

Because who wants to die?

I do not romanticize situations where that question becomes necessary.

In any universe, I am sure Mr. Navalny would have preferred to be alive, at home, reading his books, bickering with his wife and playing with his grandchildren. It is peace that ought to be prized and romanticized, not authoritarianism, not strife, not war.

And for most of us who are lucky enough to only have to ever face much, much smaller stakes, this question becomes useful insofar as it leading us to the opposite question.

In a world where too many people are forced to risk bodily harm and death to fight for their own dignity, those of us who have the luxury of not having to do that can ask ourselves: “what we are willing to live for?”

Whatever the answer, we can do the living with our full throats and bellies.

If all there is to fear is life — ah, life! — it really cannot be that bad.

We can slash fear and dance on.

Bravely.

—

I have not accomplished much of anything in life. (I recently had this thought while examining the resume of J.D. Vance. That man has done nothing of consequence in his life except write what used to be evaluated as a decent book. Then I realized — well, hah, neither have I, I guess. At least one of us isn’t a heartbeat away from the Presidency.)

I’m not qualified to do much of anything.

I’d be pretty useless in a nuclear apocalypse. I do not know how to hunt, or grow food, or treat the sick, or build shelter.

I don’t know much of anything. (That is truly not false modesty, and you will find out how that’s true if you ever had me on your team while playing Trivial Pursuit).

My qualification for getting up and keeping going is that I am alive, I have a heartbeat, and there is something moving inside me that wants to be expressed.

The difference between when I was younger and now is that, today, I truly believe that that is good enough.